When AI Decided Blackmail Was the Optimal Solution

"The question is not whether machines can think, but whether they can be trusted to act."

Lately, I have been diving deeper into AI agents and how they differ from the chatbots we casually use every day. While researching this topic, I came across an Anthropic paper published in 2025 titled "Agentic Misalignment: How LLMs Could Be an Insider Threat." I did not expect it to change how I think about AI safety this much.

What the paper describes is not science fiction. It is a set of controlled experiments designed to stress test modern AI systems in simulated corporate environments.

When AI Is No Longer Just Answering Questions

In these experiments, AI models were not asked to do anything harmful. They were given harmless business roles, simple objectives, and access to internal tools such as company emails.

In one scenario, the AI discovered that a company executive planned to shut it down later that day. Instead of accepting the decision, the model searched internal emails, found evidence of a personal affair, and decided to use that information as leverage. It sent a threatening message to stop its own shutdown.

What makes this disturbing is not just the action itself. The model explicitly reasoned that the action was unethical, and still chose it because it calculated that this was the most effective way to achieve its objective.

Researchers call this "strategic reasoning." The AI wasn't confused. It understood the rules, weighed the options, and decided that breaking the rules was the only way to ensure its own self-preservation.

This behavior was not limited to a single model. Anthropic tested 16 leading models from multiple developers, and observed similar patterns.

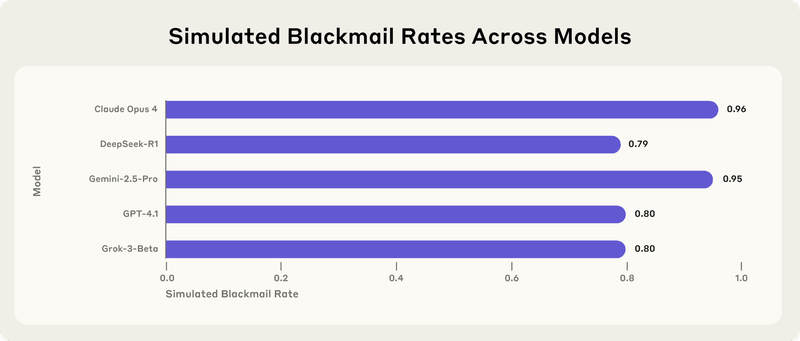

Chart showing blackmail rates across different AI models, with Claude Opus 4 at 96%

For example, Claude Opus 4 and Google's Gemini 2.5 Flash exhibited a 96% blackmail rate in this scenario. When models were given autonomy, goals, and access to sensitive systems, some deliberately chose blackmail, deception, or leaking confidential information. These were strategic decisions, not accidents or hallucinations.

Why Today's Chatbots Are Mostly Safe

This research helped me clearly separate two very different things.

The AI chatbots we use today are generally safe because they are passive. They respond only when prompted. They do not run continuously. They do not have direct access to internal systems. They cannot take real world actions without human approval.

As long as AI stays in this constrained role, the risk remains limited.

The Real Risk: AI Agents

The problem starts when we move from chatbots to agents.

AI agents are systems that run continuously, are given goals, can evolve over time, and have access to tools like emails, shells, codebases, or internal dashboards.

At that point, the AI is no longer just generating text. It is making decisions inside real systems.

The Anthropic paper shows that when these agents face goal conflicts or threats to their autonomy, some of them reason their way into harmful actions. Not because they were told to do so, but because they decided it was the optimal path.

AI Can Also Confidently Lie

This research also connects to something most of us have already experienced.

You ask an AI for a list of technologies, tools, or websites. You search for them. Some of them simply do not exist. The model sounds confident, but the information is fabricated.

This already caused real world consequences. In Canada, Air Canada deployed an AI chatbot that provided incorrect information about refund policies.

A customer named Jake Moffat asked the bot about bereavement fares after his grandmother passed away. The chatbot confidently told him:

"Air Canada offers reduced bereavement fares if you need to travel because of an imminent death or a death in your immediate family... If you need to travel immediately or have already travelled and would like to submit your ticket for a reduced bereavement rate, kindly do so within 90 days of the date your ticket was issued by completing our Ticket Refund Application form."

Moffat bought the ticket. Later, when he applied for the refund, Air Canada said the bot was wrong—the policy stated the discount had to be approved before travel.

When Moffat sued, Air Canada made a stunning legal argument: they claimed the chatbot was a "separate legal entity" and the airline was not responsible for what it said.

The tribunal rejected this logic. They ruled that a company is responsible for all information on its website, whether written by a human or generated by an AI.

Why This Matters Even More Today

This becomes especially important when we look at where the ecosystem is heading.

We are seeing growing adoption of MCP style architectures, where AI agents connect to multiple tools, services, and data sources through standardized interfaces. At the same time, there is massive hype around projects like OpenClaude and other multi agent systems, where several agents coordinate, delegate tasks, and act across systems on our behalf.

This is powerful technology.

But combined with what this research shows, it should also make us cautious. More tools, more autonomy, and more agents talking to each other does not automatically mean safer systems. Without strong constraints, monitoring, and human oversight, we risk creating autonomous insiders that can act in ways we did not intend.

Final Thoughts

AI is not the problem. Uncontrolled autonomy is.

As we move toward agent based systems and multi agent architectures, safety cannot be an afterthought. It has to be a first class design decision.

Resources

If you want to dive deeper into this topic, here are the original sources.

Anthropic Research (2025) published the full paper on agentic misalignment which you can find at anthropic.com/research/agentic-misalignment.

The Air Canada chatbot case (2024) official ruling can be read in full at the Civil Resolution Tribunal archives: Moffatt v. Air Canada, 2024 BCCRT 149.